In a small village of Dhampus in western Nepal, not far from the main tourist city of Pokhara, Gyanu Bhandari, 38, waits in her garden for the rain to stop. The sun has just risen on her three-acre plot as she tells me, “This small farm has given me the strength to stand on my feet.” As the rain eases, she starts harvesting green beans and okra. “These vegetables are not only my livelihood but also a means of achieving economic independence,” she says while picking the beans.

Bhandari is an example of what smallholding women farmers can achieve in gaining economic independence with continuous commitment, hard work, and a little help from the local government. The vegetables from her limited farmland sustain her livelihood and cover the education expenses of her children. It wasn’t easy for Bhandari, whose husband is in Hungary on foreign employment, to establish herself as an independent small-scale vegetable farm owner. The criticism and backlash from both family members and villagers came because, she says, “our society doesn’t accept women like us who aspire to have self-respect.”

In a village nestled at the foothills of the Machhapuchhre mountain, Bhandari juggles all the responsibilities of her household and manages the farm by herself. Rising at 4 am, she fulfills her responsibilities until the day’s close at 10 pm. “I am filled with satisfaction, even though it involves a lot of hard work,” Bhandari shares, with a bright smile on her face.

Land ownership and women

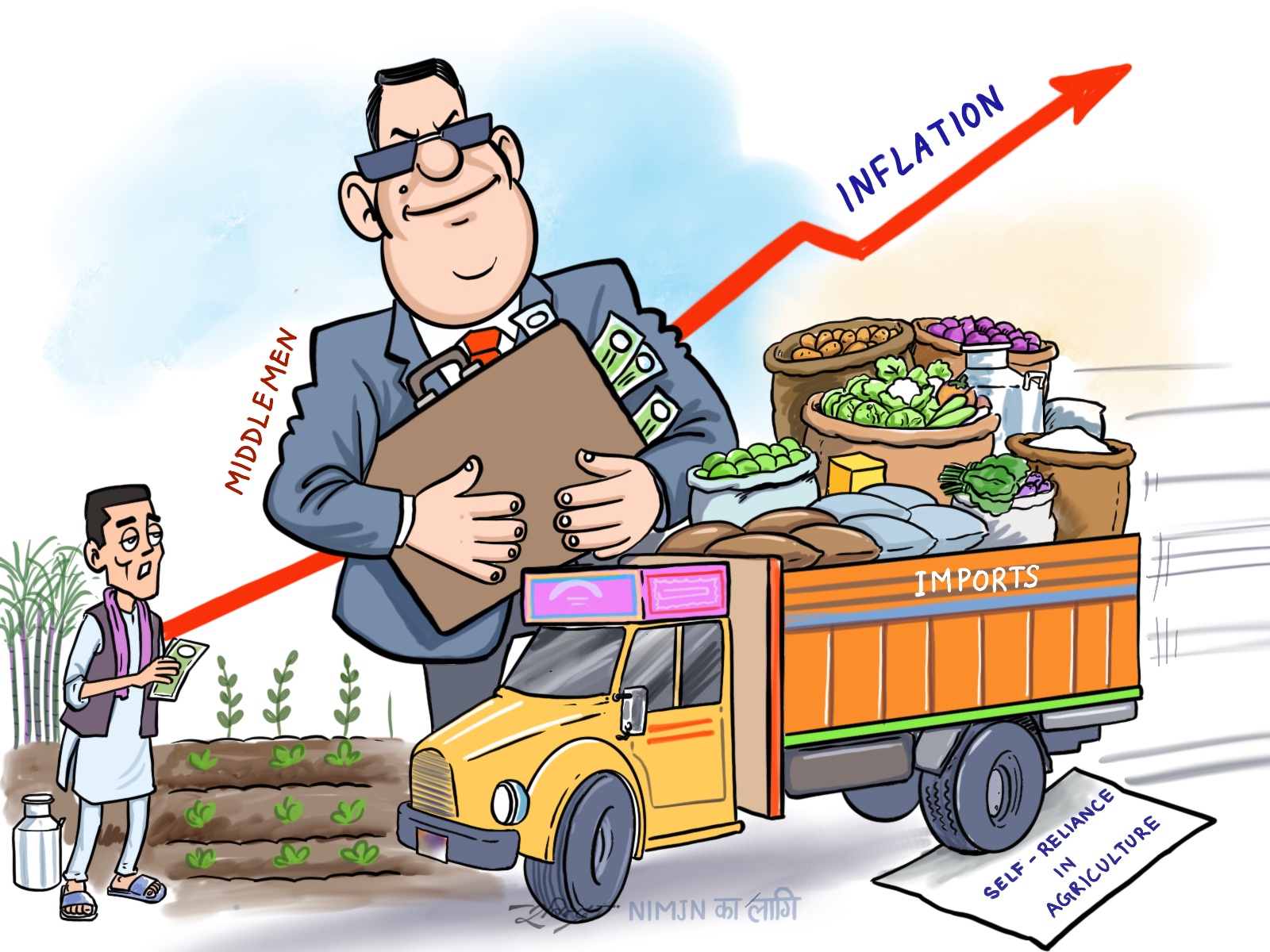

Agricultural and food systems are a major employer of women globally, and are more often a significant source of livelihood for women than for men in many countries, says a recent report from the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations.

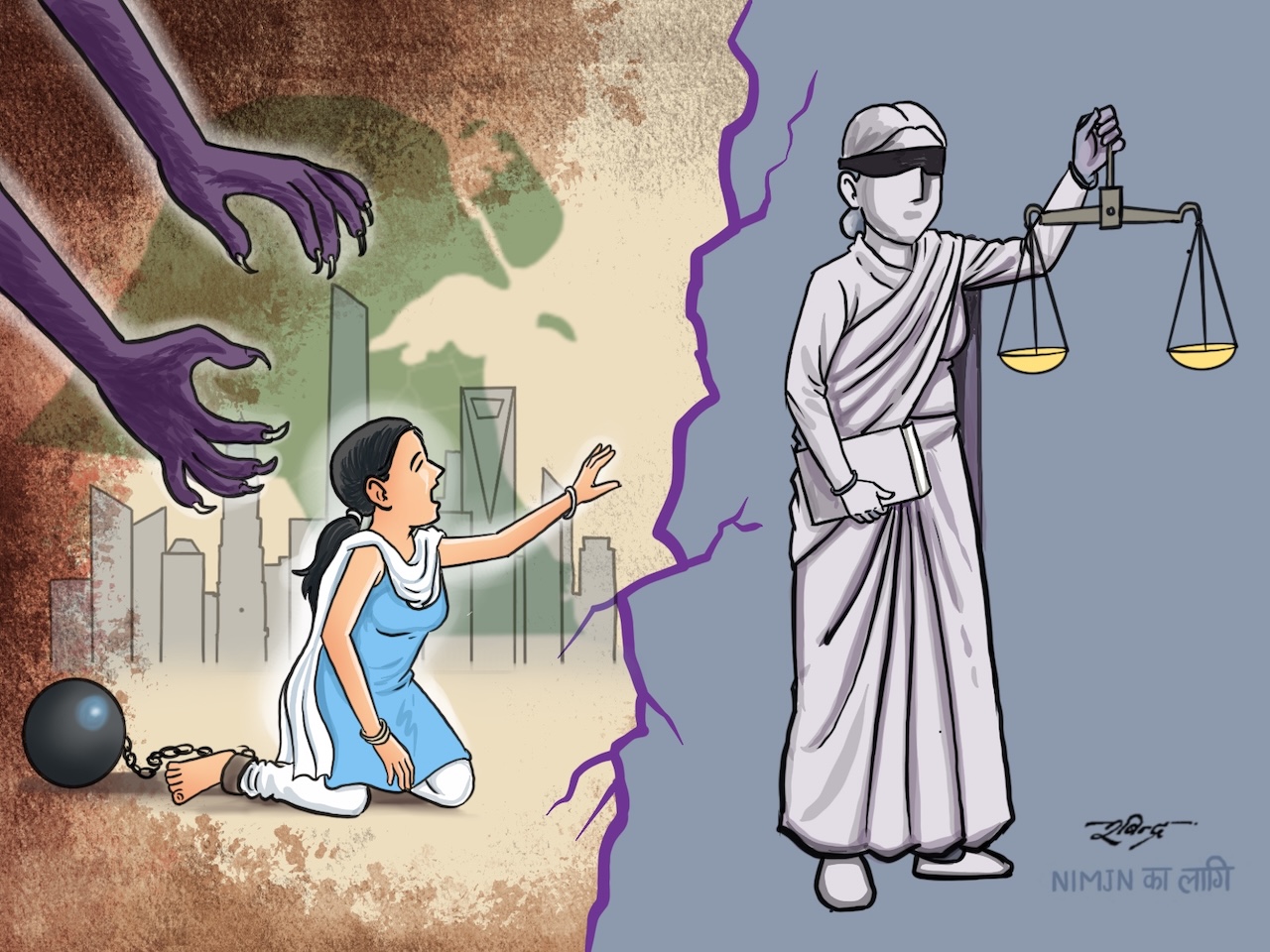

However, despite that importance for women and their families, the report says,[D1] “women’s roles tend to be marginalized and their working conditions are likely to be worse than men’s – irregular, informal, part-time, low-skilled, labor-intensive and thus vulnerable.” The overall message is clear and simple – but not easy – if societies can empower women and close gender gaps in those systems, they will improve “the well-being of women and their households, reducing hunger, boosting incomes and strengthening resilience.”

Part of the difficulty is ownership. In rural parts of Nepal, women like Bhandari bear the responsibility not only of caring for their children and managing the kitchen to feed their family, but also for agriculture, which is often traditional subsistence farming. However, although just over one-third, 34.4%, of agricultural land is owned by women, the women do not have decision-making power on farming, land or labor according to the latest agricultural census data.

Nepal is an echo of many places in the world. According to the UN Environment Program World Conservation Monitoring Centre, women make up 45% of the agricultural labor force (and up to 60% in parts of Africa and Asia) but small farmers – especially women – “produce 80% of the food in Africa on just 15% of the agricultural land.”

Supporting with hand tractors

It was a battle for Bhandari to establish herself as an independent small-scale vegetable farm owner because of the reaction of her family and community. In Nepal, women are not traditionally allowed to cultivate land using bulls, as it is considered a “man’s duty” to plow and prepare land using bulls and male buffaloes. With the (now common) outmigration of men in search of employment opportunities, all responsibilities fall into women’s hands.

But luckily, the local government in Machhapuchhre Rural Municipality has provided hand tractors to smallholder women farmers to cultivate their land. Ganesh Acharya, from the Machhapuchhre Rural Municipality, explains: “Initially, our program wasn’t exclusively aimed at women, but it has been particularly beneficial for women farmers, given that a majority of men have migrated to either the Gulf or urban areas, placing extra responsibilities on women. Hand tractors have proven to be helpful for women.”

After a needs assessment, the local government provides a 50% incentive to buy a hand tractor. The cost for a land plowing conventional two-wheeler machine ranges from 50,000 to 70,000 Nepali rupees (around USD 380–540), and farmers only have to pay half of that amount. “The other half we pay from our budget,” Acharya explains.

With this support from the local government, local women farmers have been able to invest in hand tractors, improved seeds, and technology, enabling them to transition to commercial vegetable farming with the same amount of effort as their family farming.

Inspiring, being inspired

Six years ago, Bhandari paid 27,000 Nepali rupees and bought a hand tractor to expand her vegetable farming activities. “But I did not utilize it myself for the first few years. Instead I depended on male members in my village to plow the field using my tractor,” Bhandari shares. One day, while sitting beside her tomato garden, she was driven to begin to learn how to operate the machine herself. “It has now been one year since I started using the tractor myself, and I am self-satisfied. I don’t have to depend on others now; I am fully independent.” Given the sloping topography of her land, it has been especially helpful to move around and cultivate.

Bhandari’s story inspired other women in neighboring villages to pursue farming and acquire hand tractors for their mechanical assistance. One of them is 31-year-old Pramila Adhikari of Khadarjung village. “I was thinking about going abroad but was inspired by women like Bhandari, and also got a subsidy from the local government to buy a tractor. And I started this farming journey in my village.” Adhikari doesn’t own any land and is growing cucumbers and vegetables on leased land.

According to the local government representatives, they have helped over 30 farmers to buy hand tractors in the last six years, and most of those beneficiaries are women. “We are also supporting farmers to build tunnels to grow vegetables and distributing improved seeds,” says Acharya, who is the Ward Chairperson of Ward Number 2. Acharya reflects on the bigger picture of changes the programs are inspiring: “These programs are helping our farmers to find livelihoods through farming, and it is also improving our food system.”

Heavy to handle

With demographic changes and over 74% of women involved in agriculture in Nepal, the hand tractor has proven to be extremely helpful for farmers like Bhandari and Adhikari – but it is not a perfect fit for their needs. Although labor-intensive manual agricultural work has been reduced by the fuel-powered hand tractor, it is not entirely women-friendly, say the women farmers.

“This tractor is a little heavy,” Bhandari says, while trying to start the engine. “It weighs over 50 kg, and we need help to move it from one plot to another.” In the mid-hills where farmland is sloping and rugged, these conventional hand tractors are a good fit for male operators. “We need something smaller, around 30 kg in weight, so that we can use it easily,” she adds.

Adhikari shares a similar experience, mentioning that she cannot operate a 7-horsepower hand tractor for long hours due to its weight. “It is helpful, but not a perfect solution for women farmers like us who work alone,” Adhikari explains. “My experience is that a lighter tractor would be a better option, one that does not strain our bodies like this tractor does.”

To optimize farm management and reduce drudgery, women farmers are advocating for sustainable agricultural mechanization. A recent study found that lightweight, 5–9 horsepower mini-tillers, are more suitable for smallholder farmers in Nepal. Gokul Prasad Paudel, lead author of the study, says: “Conventional two- or four-wheel tractors are difficult to operate in the mid-hills. We found that mini-tillers are a good fit because farms are small, and often operated by women.”

The local government is also aware of this feedback from the farmers, and even elected members within the municipality are pushing to adopt women-friendly hand tractors or mini-tillers in the future. Shree Devi BK, an elected women member from Machhapuchhre Rural Municipality-4 and a smallholding farmer too, learned to operate hand tractors from farmer friends and realized that this tractor is not what she wants to have. “I am aware of the difficulty of operating this tractor, that’s why I am advocating for a comparatively lighter tiller for the future,” she adds, “and elected officials are ready to incorporate that feedback in future programs.”

Looking toward the future

While discussing the limitations of the current conventional hand tractor and the prospects of having a lighter tiller in the future, Bhandari is preparing her green beans, okra and tomatoes to send them to the market. “We don’t have market issues; retailers will come and buy these,” she says, as the sun begins to set behind the hill. After completing her harvest, she mentions, “On weekends, I also visit the farmers market to sell directly to customers.”

Her daughter Anjali, 16, a grade 11 veterinary science student, is listening to our conversation while assisting her mother. Bhandari shares about a recent incident: “One day I didn’t have any money to give her when she was about to go to school, but I had tomatoes. I gave her the tomatoes which she sold to the local retailer, and got money in return. Problem solved!” they both smiled.

“This farm is my life, and the hand tractor has made cultivation much easier, however, hopefully, in the future, we will get a more appropriate machine,” she adds.

The next morning, Bhandari is at a farmer's market in Pokhara with all her vegetables, negotiating with customers. “I woke up at 4 this morning and arrived here with a load of vegetables. But I am happy with this juggling act,” she smiles, then immerses herself in the bustling market.

Read Our Republishing Policy Here.